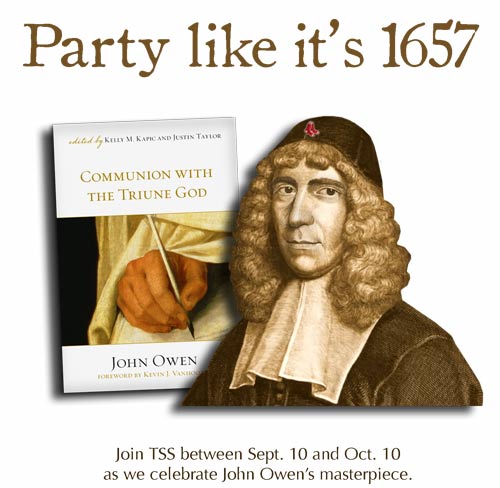

John Owen and Communion with the Triune God

John Owen and Communion with the Triune God

Interview with Dr. Derek Thomas

What comes to mind when you think of communion? Bread, wine, and religious ordinance? The following interview is for fellow 21st century pilgrims unfamiliar with the term ‘communion’ and specifically ‘communion’ with God.

October 12th is the scheduled release date of Justin Taylor and Kelly Kapic’s newest volume in the writings of Puritan John Owen, Communion with the Triune God (Crossway: 2007). Communion was first published in 1657. The original edition is in the public domain, has been printed in various shapes and sizes, and is available for free online. In the past 50 years this work has been known as the second volume of The Works of John Owen (Banner of Truth).

The 2007 Crossway edition includes several enhancements like helpful indexing, introductions, extensive outline and glossary. Owen’s work has never been more accessible for readers (see our review here).

For the next month we are taking some time to highlight Owen’s masterpiece. Today we talk with Dr. Derek Thomas to discuss John Owen and better understand communion with God.

For the next month we are taking some time to highlight Owen’s masterpiece. Today we talk with Dr. Derek Thomas to discuss John Owen and better understand communion with God.

Introduction

Dr. Thomas is from Wales and currently serves as John E. Richards Professor of Systematic and Practical Theology at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi. After pastoring for 17 years in Belfast, Northern Ireland, Dr. Thomas returned to the United States in 1996 and also serves as the Minister of Teaching at First Presbyterian Church in Jackson. He has lectured extensively on Owen (listen to his lectures on Owen here).

TSS: Dr. Thomas, it is always an honor to have you join us here on The Shepherd’s Scrapbook! Being a scholar of John Owen and well-acquainted with his works, what are your initial thoughts of this classic, Communion with the Triune God?

DT: Thank you, Tony. It is a great honor for me to join you here at The Shepherd’s Scrapbook. It is one of my favorite sites to visit.

I am also delighted to speak about John Owen. Along with John Calvin, he has been the most influential theologian in my life (at least, among dead ones!). I think I “commune” with him most days about something. That’s the great value of books. The authors may have died, but their writings live on.

I’m as excited as you about the forthcoming publication of Communion with the Triune God, after the splendid job they did with Overcoming Sin and Temptation (Crossway, 2006).

What comes to mind about Owen’s volume, Communion with the Triune God, is its essential Trinitarianism. Owen does a number of things that are important for us to see.

First, he is thoroughly indebted to Calvin and the Fathers in his Trinitarian theology. In an age when the church would find it difficult to expound the Trinity in any meaningful way, Owen assumes a line of theological continuity from the early centuries to his own day (thereby removing the charge made by Rome that Protestantism was ‘new’ and therefore suspect). He cites, for example, the classic formula of Augustine that the external acts of the Trinity cannot be divided (opera ad extra Trinitatis indivisa sunt) without any embarrassment! And, if my memory serves me correctly, we’re only a few pages into the volume!

The second thing about this volume is not only its catholicity (linking with the Fathers), but its centrality. In focusing on the believer’s fellowship with God (Father, Son and Holy Spirit), Owen is picking up what Calvin had insisted lay at the heart of the all theology – union with Christ. Owen is doing so in a more overtly Trinitarian fashion than perhaps Calvin did; but he is bringing to surface what is at the heart of God’s covenant relationship with redeemed sinners. In doing so, of course, Owen can’t help but be experiential in his theology. In that sense, Owen is a perfect example of the puritan oeuvre.

TSS: At first glance of the title people may confuse this book as a long work on prayer or the spiritual disciplines. Or it may be shelved in bookstores with purely subjective books on how to experience some divine warm-fuzzy. Communion with the Triune God is very unique. What does Owen mean when he talks about “communion”?

DT: This is a really good question! And if the publication of this volume can do something to displace these unhelpful books to which you refer, then all the better for it!

displace these unhelpful books to which you refer, then all the better for it!

Why is the reformed church so confused about reformed spirituality? This is where a volume like Owen’s Communion with the Triune God is so valuable at this present time.

Owen has a fairly complicated view of what communion in this context means. It begins with the idea of what “communion” or “fellowship” in Greek (koinia) means: to share in common with. This raises some important theological (and practical) distinctions: union and communion are not synonyms for Owen. Our union with Christ, brought about by God’s initiative and covenant. It introduces into a status from which flows (as fruit) communion with God. Kelly Kapic summarizes it this way:

- God communicates of himself to us.

- Union with Christ establishes our relationship with God.

- The resulting overflow of union is our returning unto God what is both required and accepted by him (i.e. communion). [endnote 1]

The union with Christ is brought about unilaterally; the communion on the other hand is a bi-lateral issue. Our communion with God can be affected by our sin, unresponsiveness, and especially neglect of the ordinary means of grace.

It is Owen’s Trinitarian emphasis, based to be sure on a disputed text (1 John 5:7), that enables him to expound a multi-faceted dimension to communion. Communing with the Father helps us appreciate the nature of love and reciprocate it; fellowshipping with the Son helps us appreciate and reciprocate grace; fellowshipping with the Holy Spirit encourages assurance as he draws us back to the embrace of Jesus Christ offered to us in the gospel of the Father’s love.

TSS: Communion with the Triune God is rightly hailed as a masterpiece on the Triunity of God. Why is this Triune distinction important in Owen’s understanding of communion?

DT: I have preempted this question somewhat already. But allow me to narrow the focus a little.

The obvious place to begin is to state that for Owen God is Trinitarian in nature. The only fellowship with God that is possible is with the entirety of the Godhead and therefore with each Person that constitutes the One God. If the place of any of the three persons is misconceived or denied, the gospel falls. Thus Jehovah’s Witnesses or Mormons or liberal Protestants who deny the Trinity as empty verbiage can never state the gospel properly because their view of God is all wrong.

The gospel in both its accomplishment and application involves a salvation planned, an atonement made and a salvation applied and none of these are possible apart from the work of all three Persons. For Owen, then, communion with all three keeps the gospel straight and the Christian life in good shape. From it flowed all manner of issues relating to the assurance of salvation – too often argued subjectively without recourse to the nature of salvation itself.

TSS: I’ve watched enough YouTube videos to notice that a large segment of professing Christianity in America dogmatically assert that Christianity is a relationship whereas theology is peripheral. For Owen, experiencing God personally and knowing God accurately are inseparable. Can you explain further how this is revealed in Owen’s thought and why this is important for us to grasp today?

DT: I’ll have to take your word about YouTube, but it is time for us to announce a Declaration of War against the creeping influence of Schleiermacher on modern evangelicalism.

I draw your attention to an essay by Carl Trueman called “John Owen as a Theologian” in a volume of essays on Owen, John Owen: The Man and His Theology (P&R and EP, 2002). These were lectures delivered at a conference on Owen in 2000. It says everything that needs to be said, first of all, about Owen’s distinctive theological emphases, and secondly why theology must be in the service of the experiential and not vice versa.

Owen was no different here than his Calvinstic predecessors, or for that matter, John Calvin himself. From Calvin’s opening sentence of the Institutes, which declared that nearly all the wisdom we possess consists in knowing God and knowing ourselves, comes the distinction that knowledge of God is more than knowing about God. There is a difference between knowledge by description and knowledge by acquaintance.

I had a student in my office recently who obviously loves Sinclair Ferguson. He had listened to what sounded like hundreds of Ferguson’s taped messages. I listened with interest and then (half anticipating the reaction), I said with cool detachment, “I’ve known Sinclair for 30 years and he’s a close, personal friend.” There was an awed silence! “Really!”

Well, Owen would say, Christians brought into a saving relationship with God through faith in Jesus Christ can say, “I know God – personally.” True, the descriptive “personally” is a modern one and not one the seventeenth century would have employed in quite the same way, but the intent is precisely the same.

For Owen, as for Calvin, there is no sense in trying to talk about knowing God by experience if we don’t know how to articulate who God is! The only God there is has revealed himself to us in creation and providence, but supremely in the Scriptures and in his Son’s incarnation. But to have those things clear in our minds and be able to articulate them is not yet to know God. To know God, cognitio Dei is relational knowledge, knowledge that comes to us, in the relationship of faith.

TSS: You mention the “personal” aspects of a relationship with God would have been stated differently by Owen and the Puritans. Explain this further. How is this differently stated? Why?

DT: Well, forgive me, but I think we tend to use the word “personally” in some quasi-therapeutic sense, often at some disparagement to anything cerebral or structured. The puritans adopted (on the whole) a very definite faculty-psychology in which the mind must govern the will and the affections. Personal knowledge of God comes through the integration of this faculty psychology and through some back door to the heart.

TSS: This is very helpful in light of earlier questions. Thank you! … Owen seems to balance well an understanding of our Father who remains transcendent, majestic and holy but for the saint is also their loving, adoptive Father who “from eternity … laid in his own bosom a design for our happiness.” Owen calls us to “rejoice before him with trembling” and of course says if we don’t understand the deep love of the Father we will not draw to Him in communion. Owen writes, “So much as we see of the love of God, so much shall we delight in him, and no more. Every other discovery of God, without this, will but make the soul fly from him; but if the heart be once much taken up with this the eminency of the Father’s love, it cannot choose but be overpowered, conquered, and endeared unto him” (p. 128). How does Owen excel in this theme of communion with the Father?

DT: Of course, ravishing as this language is, it should be recalled that Owen is expounding the Father’s love for us employing the Song of Solomon (Canticles) as background. This was typical of the puritans as a whole to view the Song as an allegory of salvation.

Owen is dealing with a surprisingly modern problem at this point: that in communing with Jesus it is all too possible to draw the conclusion that whereas the Son loves us, the Father is angry with us. From such a distorted view emerges a misshaped view of the gospel, of course. Jesus has no need to make the Father love us because his coming into the world is evidence of it. The Father is the “fountain” or “source” of love.

“Though there be no light for us but in the beams, yet we may by beams see the sun, which is the fountain of it. Though all our refreshments actually lie in the streams, yet by them we are led up unto the fountain. Jesus Christ, in respect of the love of the Father, is but the beam, the stream; wherein though actually all our light, our refreshment lies, yet by him we are led to the fountain, the sun of eternal love itself. … (Communion with the Father) begins in the love of God, and ends in our love to him” (2:23-24).

TSS: That’s a helpful quote that captures Owen well. Thank you! … A year ago I interviewed Kris Lundgaard, an author who has taken John Owen and rewritten his books for contemporary audiences. He said he was surprised that sales of his book on overcoming sin (The Enemy Within) far outsold his book on the beauty of Christ (Through the Looking Glass). This was to him a surprise because seeing the glory of Christ is critical in the fight against sin (2 Cor. 3:18)! It’s likely that the overtly practical Overcoming Sin and Temptation from last year will outsell Communion with the Triune God (or any other Owen titles for that matter). What are the practical implications of Communion with the Triune God to the mortification of sin and the pursuit of holiness?

DT: Well, there’s no way I can come up to Kris standard, but I along with others am so grateful for his love for Owen and his publication. He manages to make Owen appear user-friendly to those who might otherwise be intimated.

I think I can understand why a volume on mortifying sin and dealing with temptation outsells because we all feel the need for help in this area. But perhaps this is a reflection of what another theologian-preacher once called, “sanctification by vinegar,” meaning we are sometimes forced into a set of behavioral responses by the fear of being caught or the being punished rather than because we have a desire to do it.

Only by a grasp of the true nature of God and the delights of communing with him can we really respond in the way we should. Owen, as all good theologians of Paul, observed what we might call gospel grammar. The imperative must follow the indicative. Holiness follows from what grace has reckoned us to be in Christ. What this volume does is tell us who we are. It solves the identity crises which sin can so easily bring. The volumes ought to be read in that order – Communion with the Triune God followed by Overcoming Sin and Temptation. It would be the Bible’s way.

TSS: Dr. Thomas, I love this: “What this volume does is tell us who we are”! This is a helpful observation on the importance of Communion with the Triune God. … Again, thank you for joining on TSS. You are a valued friend in our ministry. Blessings to you!

—————

Related: Read our full review of Communion with the Triune God.

—————

[endnote 1] Kelly Kapic, Communion with God: The Divine and the Human in the Theology of John Owen [Baker Academic, 2007], 157.

Interview with Dr. Leland Ryken

Interview with Dr. Leland Ryken

WHEATON, IL — Behind the books on our shelves are dozens of visionaries, writers, editors, graphic artists, printers, and marketers hard at work. One goal of The Shepherd’s Scrapbook is to introduce the people and organizations behind the books.

WHEATON, IL — Behind the books on our shelves are dozens of visionaries, writers, editors, graphic artists, printers, and marketers hard at work. One goal of The Shepherd’s Scrapbook is to introduce the people and organizations behind the books.

John Owen and Communion with the Triune God

John Owen and Communion with the Triune God

displace these unhelpful books to which you refer, then all the better for it!

displace these unhelpful books to which you refer, then all the better for it! Book review

Book review The printed ESV LSB will be available on Sept.

The printed ESV LSB will be available on Sept.

Book announcement

Book announcement